A Race Against the Bathroom

Somewhere in the southern reaches of the Dominican Republic, a limestone cavern spent twenty millennia guarding secrets that would make even the most seasoned paleontologist’s jaw drop. Then one day, it nearly became someone’s toilet.

The cave known as Cueva de Mono had quietly accumulated layer upon layer of prehistoric remains while civilizations rose and fell above ground. But when researchers from the Field Museum in Chicago arrived for what they assumed would be another routine excavation, they discovered that a local resident had built a house near the entrance and was preparing to convert the ancient repository into a septic system.

What followed was essentially a paleontological heist—a desperate scramble to extract as many fossils as possible before modern plumbing could erase epochs of natural history. The scientists had no idea that their rescue mission would uncover one of the strangest ecological stories ever recorded in stone.

When Owls Ruled the Night

To understand what makes Cueva de Mono so remarkable, you have to imagine the Caribbean island of Hispaniola as it existed during the late Pleistocene. The landscape was wilder then, populated by creatures that seem almost fantastical by modern standards. Among them were barn owls far larger than any living today—imposing nocturnal hunters that dominated their ecosystem.

These colossal predators made the cave their stronghold. Generation after generation, they roosted within its protective walls, venturing out under cover of darkness to hunt the small mammals, reptiles, and birds that populated the island. After each meal, the owls would regurgitate compact pellets containing the indigestible remains of their prey—bones, teeth, and fur compressed into tidy packages that dropped to the cave floor like organic time capsules.

Over centuries, perhaps millennia, these pellets accumulated. Rainy periods came and went, depositing carbonate layers that separated the deposits like pages in a geological book. The result was a stratified record of everything the owls had consumed: rodents, sloths, turtles, crocodiles that had stumbled into the darkness, and more than fifty distinct species in total.

But the owls weren’t the only tenants exploiting this underground ecosystem.

Nature’s Most Unexpected Real Estate

Dr. Lazaro Viñola-López had spent years exploring Cueva de Mono, navigating past tarantulas whose eyes gleamed in his headlamp as he descended the ten-meter tunnel that led to the fossil deposits. His primary interest was mammals—specifically, reconstructing what the island’s prehistoric mammal community looked like based on the prey remains left behind by those ancient owls.

Then something caught his attention that changed everything.

As he examined the jawbones of small mammals, Viñola-López noticed that the empty tooth sockets contained sediment that didn’t look randomly deposited. The material inside appeared deliberately placed, smoothed and structured in ways that defied simple geological accumulation. The observation triggered a memory from years earlier, when a colleague had shown him the fossilized remains of ancient wasp cocoons.

The realization hit like a thunderbolt: these weren’t just sediment-filled cavities. They were nurseries.

The Bone Nesters

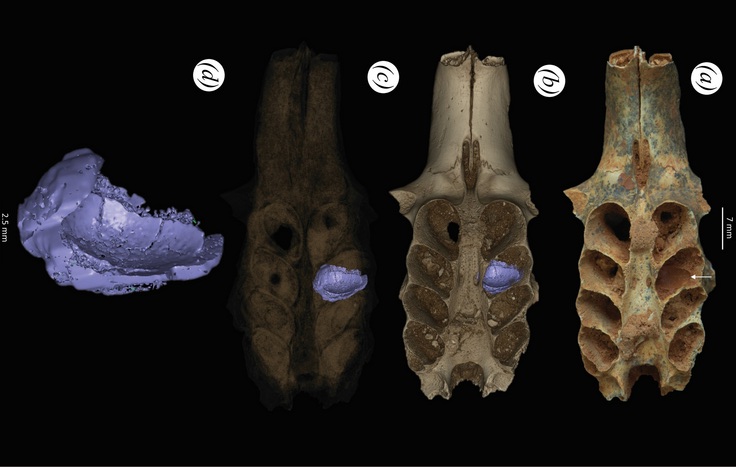

Using CT scanning technology, the research team X-rayed the specimens from multiple angles, building three-dimensional images of the mysterious material inside the tooth sockets without disturbing the delicate evidence. What emerged from the scans confirmed Viñola-López’s suspicion.

Ancient bees had transformed the discarded bones into maternity wards.

The shapes and internal structures matched perfectly with nests created by modern solitary bee species—insects that mix saliva with soil to construct individual chambers for their eggs. But these prehistoric architects faced a challenge that forced them to innovate. The landscape surrounding the cave apparently lacked the soft topsoil that their descendants use today. What the cave did have, in abundance, was fine silt and thousands upon thousands of bones with conveniently sized hollow spaces.

The bees adapted. They claimed the empty tooth sockets of owl prey as their own, filling them with carefully constructed mud chambers where their larvae could develop in darkness and safety. It represents a behavior never before documented in the fossil record—burrowing bees that built homes not in earth, but in death.

Ecosystem Archaeology

What makes this discovery particularly valuable extends far beyond its novelty. The intersection of giant owls and resourceful bees offers scientists a window into how prehistoric Caribbean ecosystems actually functioned.

Understanding ancient environments requires more than just cataloging which species existed. Researchers need to know how those species interacted, how they influenced each other’s behavior, and how they responded to environmental pressures. The Cueva de Mono deposits provide exactly this kind of information.

The owls shaped the physical environment inside the cave through their predatory habits, creating conditions that allowed the bees to thrive in an otherwise unlikely location. The bees, in turn, left behind evidence of their adaptation strategies that would have vanished completely in typical fossilization scenarios. Neither story could be told without the other.

Whether the bone-nesting bees belonged to a species still humming around Dominican flowers today or disappeared alongside the giant owls remains unknown. Many of the mammals whose bones served as nurseries have long since vanished from Earth. The bees may have followed them into extinction, or their descendants may have simply returned to more conventional nesting habits once topsoil became available again.

The Bigger Picture

For Viñola-López, the discovery underscores a lesson that paleontologists sometimes forget in their quest for impressive skeletons. The small, seemingly insignificant traces left behind by invertebrates can reveal as much about ancient worlds as any dinosaur bone.

Insects rarely fossilize well. Their soft bodies decay quickly, and even their nests typically crumble before they can be preserved. But trace fossils—the indirect evidence of animal behavior—can survive when the animals themselves cannot. A tooth socket lined with ancient bee spit represents exactly the kind of unconventional preservation that makes paleontology equal parts detective work and serendipity.

The Cueva de Mono research team has since cataloged thousands of specimens from the cave, ensuring that the site’s scientific treasures won’t be lost to development or neglect. The local resident’s septic tank plans, thankfully, never materialized.

Lessons from the Darkness

There’s something almost poetic about the chain of events that preserved this particular slice of prehistory. Giant predators consumed smaller creatures and left their remains in a dark chamber. Tiny insects discovered those remains and repurposed them for new life. Geological processes sealed everything in place. And twenty thousand years later, a researcher with sharp eyes noticed that the dirt inside some old teeth looked a little too organized.

Every fossil deposit tells a story, but Cueva de Mono tells dozens of interlocking stories—a narrative web connecting hunters and prey, opportunists and innovators, the living and the dead. It reminds us that ecosystems are never simple arrangements of isolated species. They are dynamic systems where every action creates ripples that other organisms learn to ride.

The giant owls of Hispaniola have long since fallen silent. Their prey species largely followed them into oblivion. But somewhere in the shadows of a Caribbean cave, preserved in the very jaws of the devoured, lies proof that even in the darkest places, life finds a way to build something new.